Founding

I have been up all night, trying to draft this manifesto. But no unbounded pride buoys me up, only caffeine and the expectations of my comrades. Earlier today, these comrades, now all sucking their pillows in sleep, sent me an outline of what they wanted, a rough sketch of grand plans “to destroy the old world of 1, 2, & 3”—normal stuff for avant-garde groups like ours. But—blast! I have accidentally dumped a full tumbler of coffee on their manuscript, which they had penned on fine parchment with a dull pheasant feather quill and some homemade India ink. (Those guys. Always trying to be Voltaire.) Now their words are a murky morass of shifting, competing signifiers, a grapheme gruel in midnight hues. And I am left without a clear blueprint. I hardly know where to begin.

Since it’s getting late, and I’m getting desperate, I’ve decided to pilfer the manifestos of other radical, avant-garde groups—Futurist, Vorticist, Surrealist, Dadaist, Unabomberist, etc.—for ideas of what kind of diatribe is expected of me. Yet, looking over these screeds now, each seems at turns effective and ineffective, at once wholly convincing and utterly ridiculous. And while such antitheses might be perfectly acceptable to me, I fear my co-conspirators would not approve. So I will try my best to pinch the best bits from each. Maybe then, by my morning deadline, I’ll have penned a kind of avant-garde manifesto writer’s how-to manual, which might itself be an avant- garde manifesto of sorts for even the most finicky fringe group to demolish old orders and establish new ones with, though it will have been totally plagiarized.

Rule One

Drink coffee

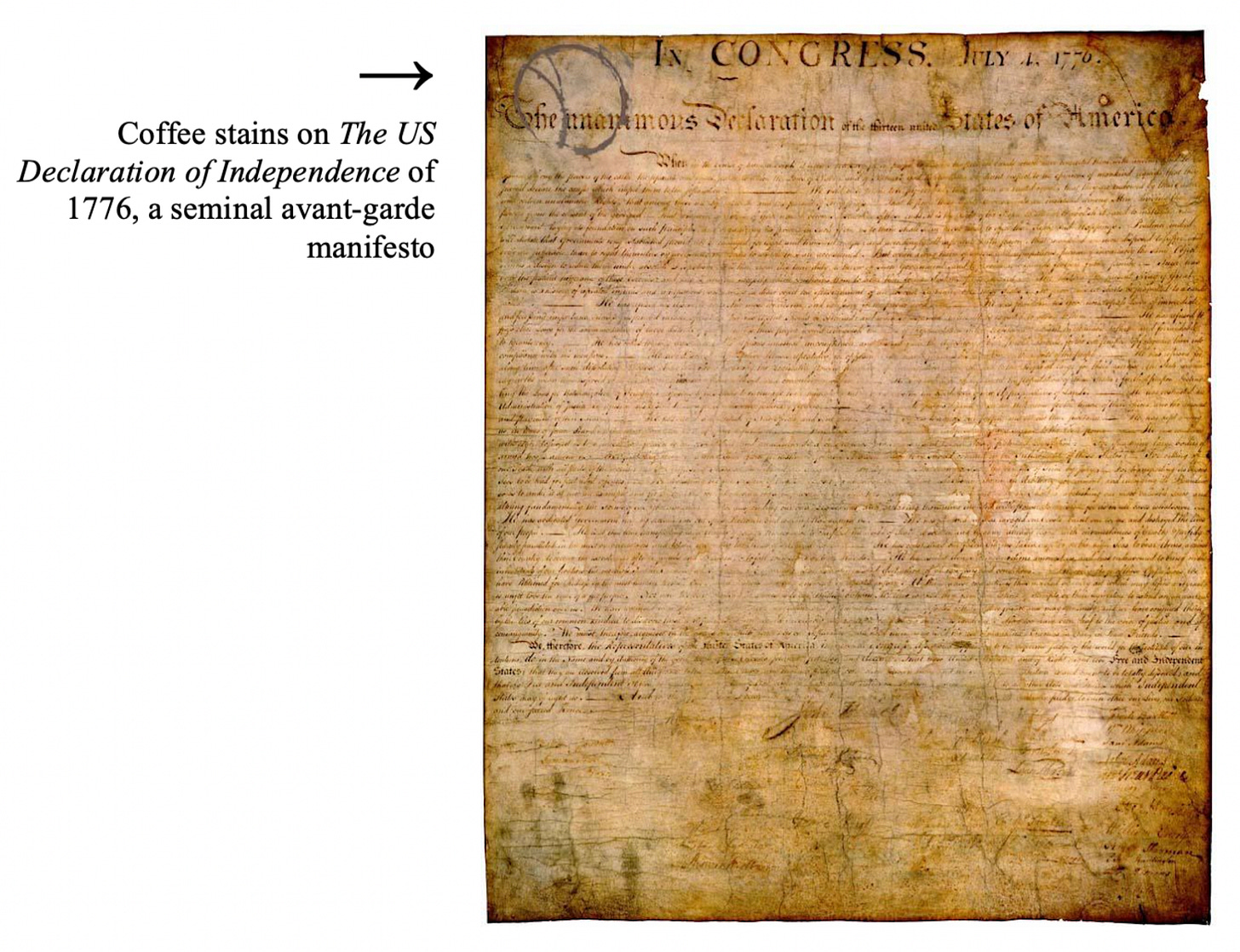

This rule might surprise you. For hasn’t coffee only been catastrophic in relation to our project thus far? Yet, after much research, I have been won over by the stuff. May I start by mentioning in coffee’s defense that the opening of England’s first coffee house coincided with a spike in radical pamphleteering, which, in turn, led to the monarchy- toppling English Civil War? Or that, over the ensuing decades, as London coffee houses became increasingly popular, they increasingly became breeding grounds for post-war radicalism? So threatening were these caffeinated establishments’ anti-establishment tendencies that in 1676 Charles II felt compelled to temporarily close them, seeing them as “places where the disaffected meet, and spread scandalous reports concerning the conduct of His Majesty and his Ministers.”1 It should come as no surprise, then, that in the next century Benjamin Franklin turned to these same London coffee houses to sharpen his radical-pamphleteering skills, which through him passed into that seminal avant-garde manifesto, The American Declaration of Independence of 1776. Nor is it particularly surprising that that manifesto was first presented to the public at Philadelphia’s Merchant’s Coffee House.

This caffeinated trend among the avant-garde continues into the next century. In 1876, a hundred years after the birth of American independence, the founder of Futurism was born, F.T. Marinetti. Marinetti’s Futurist Cookbook calls for “salami immersed in a bath of hot black coffee flavored with eau-de-Cologne.” He once referred to a waiter’s inadvertent juggling and spilling of coffee as a “Futurist dance” or a “very theatrical form of Futurist aviation.” In a Futurist treatise on noise, we find “insomnia newsboys-scream glory domination coffee war-stories.” Indeed, Marinetti even imagined coffee to be a key ingredient of Marinetti, the rousing, alarming Marinetti before whom so many trembled: apparently he “liked to describe himself as the ‘caffeine of Europe’.”5 And his fellow Futurists who helped him issue his manifesto’s cultural wake-up call clearly felt his caffeine-like influence. “We have been up all night, my friends and I,” Marinetti says in the Founding section that precedes the Futurist Manifesto of 1909. “An immense pride was buoying us up, because we felt ourselves alone at that hour, alone, awake, and on our feet.”6 Fuelled by coffee, Marinetti’s manifesto runs rife with wakefulness and restlessness—in opposition to that dreamy repose, not just of the people sleeping all around him who were not up writing Futurism’s manifesto, but particularly of the 19th century Romantics. “Up to now,” Marinetti declares, “literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia.”

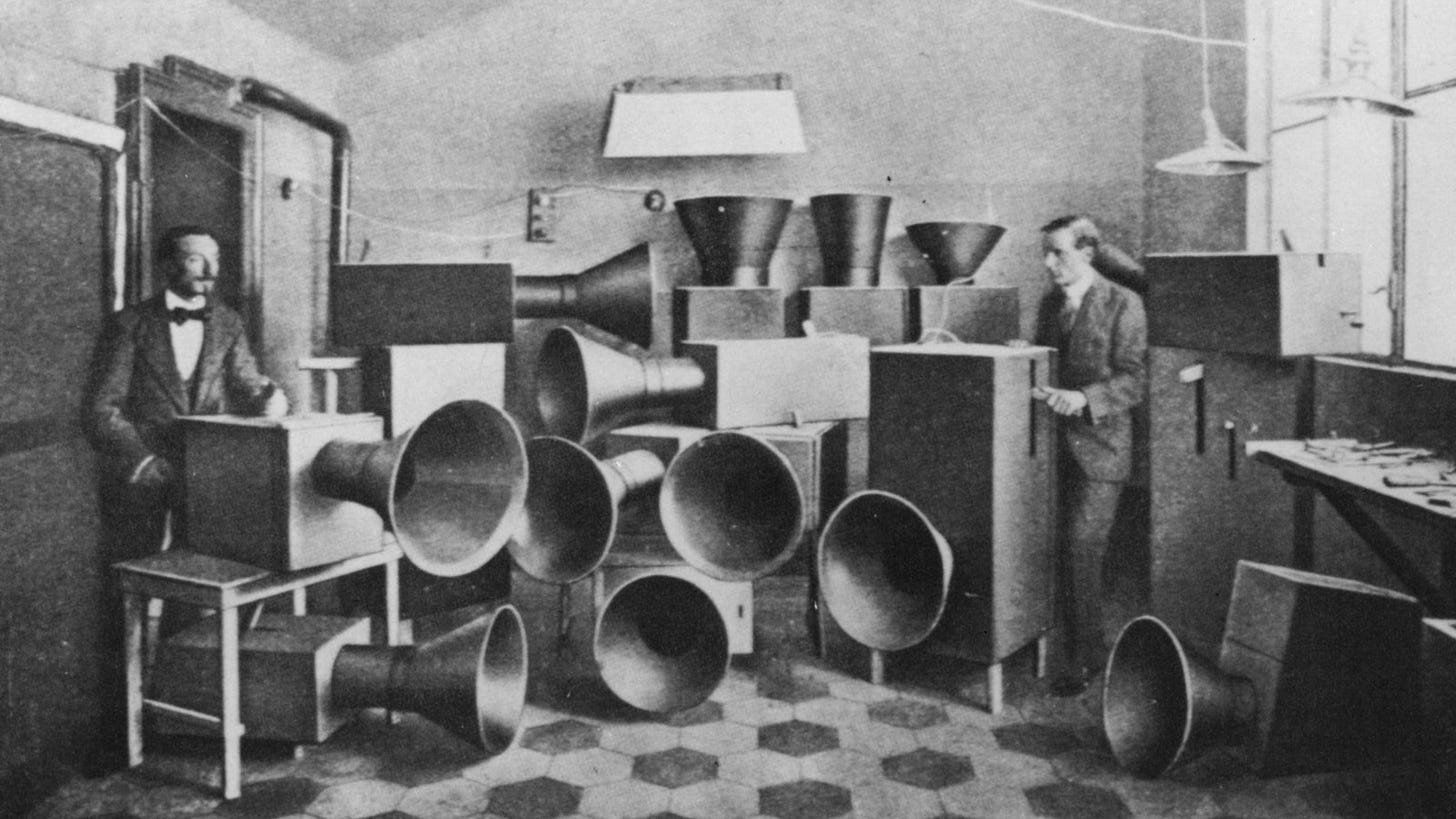

Critics have long held the Futurists to be early-twentieth-century technophiles, advocates of various technological prostheses: trains, autos, telephones, and radios. The Futurists hoped that, with these gadgets ever more integrated into our lives, we modern humans would be able to transcend the spatiotemporal and biorhythmic boundaries that had heretofore cribbed our spirit. Thus Marinetti’s racing auto, in opening up new distances and speeds, becomes, according to American historian Jeffrey Schnapp, the “emblem of the transformation of pre-modern into modern man.”8 But as much as the Futurists adopted such prostheses to enhance the physical capabilities of the body, they embraced coffee as a kind of prosthesis to the brain and the central nervous system, allowing their conscious minds to abolish the natural boundaries of night and the circadian rhythms of sleep. When up all night on a long, high-speed road trip, or when up all night just writing about one, what better companion than a nice cup o’ joe? It is likely no accident, then, that Marinetti’s description of his hot rod, with its “explosive breath” and “machine gun fire…more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace,”9 so closely matches Balzac’s iconic description of the violent effects of caffeine, where “logic’s artillery rushes out with its train and canon-cartridges” and “the vigil begins and ends with torrential downpours of black water, just like the battle with its black powder.”

And speaking of black powder: that the Futurists incorporated so much militaristic imagery into their coffee-fueled 1909 Manifesto seems now prophetic. For soon the Great War started, forcing many of Europe’s avant-gardes to remove themselves to—where else? —the coffee houses of neutral Switzerland. In Zurich’s famous Cafe Odeon, the Dadaists made their first stand against, not just the war, but against all long- standing traditions of civility and normality. After the war, coffee continued to give grounds, as it were, for manifestos to debate big ideas and arrive at new, groundbreaking places. Such was the case with Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” often called “the manifesto of the Lost Generation,” in that it breaks with many of the conventions of traditional poetry. The effects of the coffee consumed in the Hofgarten at the beginning of the poem are felt almost immediately, causing the narrator to read, and presumably write, “much of the night.” And I recollect how, just yesterday, while drinking coffee on Denmark Street, I saw someone tack on the café wall a coffee-stained document, “A Radical Manifesto for the New Millennium, by S. Brian Willson.” It seems that wherever coffee is served, so too is served the long-held tradition of overturning long-held traditions. Coffee giveth and coffee taketh away. For didn’t it bring me to this pass by destroying the outline of my comrades who are now resting comfortably in their beds, like the mindless automatons they are, while I stay up all night, with the help of coffee, to write this damned thing?

Rule Two

DO NOT obscure your radical manifesto with PYROTECHNICS.

Wyndham Lewis, in Blasting and Bombardiering, describes an odd encounter from his soldiering days, when, in the midst of leading troops through clockwork gunnery maneuvers, some superior brass accosts him about his other life as an artist: “Bombardier…what is all this Futurism about?” Lewis, standing at attention, in uniform, with “rifle on shoulder and heels together,” is appalled by the impropriety of the question, of the sudden meeting of his militaristic and artistic lives. He says “this Jack-in-office had no right really to catch me in that attitude, since […] it was wholly unsuited for expounding on the mysteries of an esoteric technique.”14 Continuing, he declares that the “parade ground was a place for arms, and not a forum for civic discussion.”15 But why would Lewis imply art and war are mutually exclusive, when in his younger years he had sought to conflate them? Lewis’ manifesto, published in Blast! in 1914 eagerly expounds a literary militarism. The incendiary, Balzacian rhetoric of Marinetti’s dispatch of 1909 excited Lewis so much that he led England’s nascent avant- garde, the Vorticists, into the new fiery fray. How could Lewis resist? “We want to glorify war – the only cure for the world,” Marinetti raged. “Let the good incendiaries with charred fingers come! Here they are! Heap up the fire to the shelves of the libraries!”16 Together, Marinetti and Lewis armed the avant-garde manifesto with the mortar round and the machine gun. Lewis’ incandescent cannons in Blast! pulverize vast epochs: “BLAST years 1837 to 1900,” and bohemian socio-cultural castes: “BLAST— Pasty shadow cast by gigantic BOEHM.”

Perhaps the very name avant-garde presaged the caustic militarism of Marinetti’s Futurists and Lewis’ Vorticists. Whereas as the military avant-garde formed the leading fringes of an attack unit, where one would find the most highly trained soldiers, the historical or artistic avant-garde imagined themselves as the radical artistic elite on the leading fringes of cultural society, even reality. There they sought to carry out their only mission, to rupture prescribed cultural boundaries that they, on the leading fringe, were always bumping up against. There Marinetti’s fetishization of the racecar and locomotive ruptured the sleepy library and museum culture of bourgeois Italy. There his technological prostheto-centrism exploded the romantic ideal of the unified body, the “nontechnological subject.”18 The manifestos of the Futurists and Vorticists even seem eager to break out of their prescribed limitations as words on paper. Thus their fiery rhetoric does not merely describe their authors’ tactics for exploding norms, but performs them.19 The oft-cited typographical innovations of these groups evince the desire of the avant-garde to issue words that transcend their status as such. Blast’s bon mots, writ large in explosive BOLD CAPITOLS playfully perform the bombing raids implicit in its radical bombasticism. Lewis and Marinetti imagined that the red glare of incendiaries would come as a package deal with, and shine glowingly upon, their radical manifestos. But things didn’t quite work out that way. From what I can gather, the Great War and its pyrotechnics recontextualized the avant-garde’s cultural locale, rendering its revolutionary agenda a fantasy bubble already burst. For suddenly, after the first few days of August 1914, exploding bodies became the norm; the leading edge of actual armies, armed with actual incendiaries, was rupturing boundaries all over Europe. Soon these tropes of troops rupturing boundaries and exploding bodies, as the new status quo and thus the new passé, were no longer under the jurisdiction of the avant-garde elite; they had been appropriated by the masses.

Marinetti probably knew this would happen. For as much as his 1909 manifesto’s militarism enacted Futurism’s revolutionary paradigm, it enacted Marinetti’s ploy to grab the attention of as many people as possible. For he believed that the common ear and eye are not particularly sensitive ears and eyes, that they essentially need to be yelled at, that they need to have things SPELLED OUT for them with the subtlety of hand-grenades. He believed that if he wanted to achieve his mission of popularizing the act of exploding boundaries, say, between high and low art, he would have to fill the pages of the popular press with the most fulminating bombasticism he could muster. So he did. And, in a sense, it worked. He got the public’s attention. But Marinetti had to know, after capitalizing on Europeans’ readiness to tune-in to his manifesto-violence, that the louder and brighter violence in the bombs of World War One were bound to steal the show. The years 1914 to 1918 testify to lowbrow culture’s eagerness to be the captive audience par excellence, reactive to big guns. And any raised brows of critique at that eagerness sunders high and low culture all over again. Which is what happened.

For, by 1918, the Dadaists started issuing radical manifestos that parodied Marinetti’s incendiary rhetoric, thus driving a wedge between their group and Futurism/Vorticism, which they felt had become, because of the war’s violence, too affiliated with what was now the mainstream: “To launch a manifesto” they mocked, “you have to want: A. B. & C.” and “fulminate against 1, 2, & 3.”20 The “real” violence of the war had trumped the artificial violence of incendiary words, so much that, after the war, Lewis complained of the distinct feeling of having had his voice smothered. “No sooner had I become famous, or rather notorious, than the War came with a crash, and with it, when I joined the army, I was in a sense plunged back into anonymity once more.”

And perhaps this is why, when the brass accosted him about Futurism, Lewis got so irritable. The war did so much to make Futurist violence passé that many of the avant- garde who had affiliated with it prior to 1914 eventually became embarrassed by it and wanted to distance themselves from it, or, when they could, rewrite their more scathing manifesto tracts to tone them down a few notches. In 1926, when Ezra Pound rewrote poems that had appeared in Blast!, we find the all-caps portions of “Salutation the Third,” such as in “HERE is the taste of my BOOT…CARESS it, lick off the BLACKING,”22 are put into lower case, divested of explosive typography. Furthermore, certain of the poem’s more scathing lines, such as, “Let us SPIT upon those who fawn upon the JEWS for their money,” becomes, merely, “Let us spit upon those who pat the big-bellies for profit.”

The former explosive rhetoric raised in people’s minds an association with the war, before which they inevitably paled and blanched. Thus the Futurist/Vorticist literary cannons were largely disarmed, circumvented like a misguided Maginot Line of signification.

Just like the manifestos of the Vorticists/Futurists, the Unabomber Manifesto of 1995 compromises its own radicalism by the addition of a pyrotechnics display. Like the Vorticists and Futurists, Ted Kaczynski did not think that in and of themselves his words would get, or perhaps even warrant, the public’s attention. He seemingly felt impotent without the prosthesis of incendiaries: “In order to get our message before the public with some chance of making a lasting impression, we’ve had to kill people.”25 But his explosives were not merely typographical. They consisted of an actual bombing campaign. His mail-bombs, in the rustic delivery system of carved wooden boxes, were otherwise tech-savvily constructed. This of course ironic, considering how loudly the Unabomber Manifesto fulminates against the military-industrial complex. Its juxtaposition of pro- and anti-technology tendencies confused the public enough, without them then having the moral dilemma of the bombs actually detonating, after which they felt armored against anything the manifesto itself might have had to say.

All of this is to say that, because Kaczynski’s manifesto came equipped with its own Great War, (because it had already been contextualized by his 17-year stint as one of the CIA’s most wanted terrorists, and because the Times and Post editors agreed to publish his manifesto only under the duress of threats that that campaign would continue), he did not have to wait for a war to start for popular interest to focus more on bombs than bon mots. It happened right away. So, though Kaczynski’s bombing rampage succeeded in getting his manifesto published, it ultimately backfired because it distracted the world from the avant-garde performance of his letters on the page. He would have been better off with a smaller readership that could actually see his words than what he got: millions who just saw smoke. In sum, Pyrotechnics and other such ham-fisted extravagances ultimately deafen, blind, and generally numb the receptors of the populace to the subtleties inherit in any radical agenda. Surely, then, radical manifesto writers who employ incendiaries should reap what they sow and [insert nuclear hellfire].

Rule Two-and-a-Half

DO NOT use FRENCH expressions.

This interdiction, à propos, simply commemorates some far-distant historical events. The first two, au bout du compte, contrast each other:

1) In 1657, the English Parliament offered monarch-toppling Oliver Cromwell the English crown; he refused it.

2) In 1804, the French Senate offered the monarch-toppling Napoleon Bonaparte the French crown; he accepted it—and crowned himself Emperor.

This simple juxtaposition illustrates the not-so-slight tilt of French towards tyrannical elitism. The Norman Conquest of England located French within pampered aristocracies from a very early stage, as William the Conqueror and his barons imposed their language, from the top down, on the English masses. And even when we look to the other hand, to radical groups on the fringes of acceptable society, there too we find French installed as hegemon, as the lingua franca of the most elite ranks of the avant-garde. Marinetti, par example, showed his contempt for the lowly English by delivering his London lectures in French. We can’t abide hegemonic cultural paradigms, especially among those groups who seek to destroy the same. So keeping all French expressions at bay will give your manifesto carte blanche to expound an ever more radical radicalism instead of just mouthing a regurgitated Futurism, which is now already a hundred years passé.

Rule Three

The Anti-Dialectic: DO NOT use QUOTATIONS.

“To launch a manifesto, you have to want: A. B. & C.,” and “fulminate against 1, 2, & 3.” This Tristan Tzara says, mockingly, in his Dadaist Manifesto of 1918.

“I write a manifesto and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestos.” He also says.

Dadaist critiques of prior manifestos stem from that group’s rejection of the logic of territoriality. Tzara held that the Futurist/Vorticist manifestos’ drawing of dividing lines between accepted and violently rejected dogma was too much a process of rational thought, which he viewed with suspicion, holding it to be responsible for Europe’s seemingly endless and pointless intellectual debates and armed conflagrations. Tzara thus resisted the competitive nature of dialectics, which pitted intellectual camps against each other, each vying for control of the territory of the mind, and imagined Dadaism as outside of dialectical rationalism. Answering dialectical debates dialectically, on their terms, he thought, would merely affirm and reinforce the context in which rationality is positively valorized.

The Dadaists inspired new avant-garde groups who refused to play the rational- thought-driven game of wanting A, B, C and scorning 1, 2, 3, so evident in prior avant- garde manifestos. For, isn’t it much more irrational and therefore more radical to want A, B, π? Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 imagines a dreamy world beyond the reign of logic. Action-based groups like the Situationists and Fluxus similarly tried to remove themselves from the rational systems of modern daily life.

—”Ah-ha!” You might at this point blurt out, pointing your finger accusingly, thinking you have caught these manifestos in a contradiction. “Aren’t these new avant- gardes’ rejections of rationalism themselves mere rational responses to a world in which rationalism is thought to be too dominant and domineering? And how can one claim to be against dialectic, when being ‘anti-dialectic’ itself puts one in a dialectical position, pitted against dialecticism per se?” But silly you. You think that being thus contradictory is some kind of liability, when a true Surrealist or Situationist wears contradiction on their sleeve like a badge of honor, seeing it as a way to reassert avant-garde irrationality all over again. For only a rational-minded person would think that irrationality fights rationality in an overarching dialectical paradigm. Meanwhile, members of the avant- garde boldly imagine a world where the stance of being against rationalism and dialectical arguments per se somehow evades being itself rational and dialectical.

Accordingly, the Situationists perform many such exercises in contradiction in order to self-medicate their own rationalist infections. For example, their 1960 manifesto condemns those who focus merely on the management of that which already exists. This might at first be taken as generic, avant-garde boilerplate, not unlike that found in prior avant-garde manifestos, where the modern, technologized world is so corrupted with rational thought that any attempt to manage or improve it only perpetuates its corruption and, again, reinforces the context in which rational thought is positively valorized. And yet, these Situationists maintain, the pathway to the verdant, wild and weedy meadow beyond the modern, technological world derives from contradictorily embracing and endorsing the modern, technological world yet more: in their 1960 manifesto they prophesy that all its oppressive machinery will only fall away when the automation of production becomes so prevalent and so efficient that it renders human labor obsolete, freeing us to go berserk.28 This display of simultaneous pro- and anti- technology instincts makes more sense as a performance of self-contradiction than it does as an actual strategy, since there is no reason to believe that an automated system would let us run free from its rein once we allow it to reign.

But The Situationist Manifesto of 1960 contradicts itself in another, more confounding way. Do you recall its condemnation of those who merely manage that which already exists, noted in the preceding paragraph? Well, this avant-garde advice apparently also applies to cultural productions. The thinking is that, by focusing overmuch on the art of the past, we tend to undermine, compromise, or stifle our own current creative spirit. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto of 1909 claims something more or less along these lines: “To admire an old painting is to pour our sensitiveness into a funeral urn, instead of throwing it forward by violent casts of creation and action.” True to this rule of thumb, we find that many of the Situationists’ situations vent hostility upon the cultural productions of the past. Indeed, the Situationists famously published a tome, entitled (in French!) Mémoires, which comes wrapped in a sandpaper book cover—that it might more effectively erode other books placed next to it on the library shelf. Considering this well-established anti-establishment tendency of the Situationists, though, it seems out of character and wholly inappropriate that, in the confines of their manifesto, they should quote from an already-established author of an entirely different manifesto, Frederic Engels. With no apparent sense of irony, the Situationists proclaim, using Engles’ words, their preference for a society that “reorganize[s] production on the foundations of a free and equal association of producers.”29 Here’s the full quote from Engels:

The society which organizes production anew on the basis of free and equal association of the producers will put the whole state machinery where it will then belong—into the museum of antiquities, next to the spinning wheel and the bronze ax.

Citing Engles here seems utterly self-defeating. For how can a manifesto prize organizing production anew “on the foundations of a free and equal association of the producers” and at the same time quote an old, dead author, thus privileging him above all the other authors that it cruelly leaves unquoted? How could free and equal association be promulgated by such a clear instance of discrimination? The Situationists here place the mighty Engles on a high velvety pedestal, embalm him like some god-king of old, rendering him a museum piece. And we are right there in the museum too, kneeling, subservient, looking up at him, dumbstruck and prostrate; our nose up to the glass, pig- like. A true avant-garde group should be focusing on its own ability to say rather than passively looking to the great minds of the past to say things for it.

No one said this better than Ralph Waldo Emerson. In his 1837 manifesto, entitled Oration Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society, Emerson urges the would- be self-reliant scholars of his day to stop listening to “the courtly muses of Europe.” He reminds them that “meek young men” who “grow up in libraries” often forget that Cicero, Locke and Bacon were only young men in libraries when they wrote [their] books.”

So we should listen to a great writer of the past like Emerson when he says we shouldn’t listen to the great writers of the past. For quoting “great writers” in an avant- garde manifesto exposes one’s lust for intellectually ground already taken, and by now well-trodden. Thus will pre-existing thoughts stifle new ones. When we call upon the old literary canons to rise and swivel at our command, either for or against, we reinstall dialectical debates and the passé Great War all over again. I can see little difference between such manifesto methodology—of bringing out the big guns to impress your stunned readership—and Kaczynski’s firebrand bombasticism. And we know how that story ended.

Rule Four

EVERYONE deserves a say: DO NOT publish your manifesto.

The self-reflexive illogic of Situationism and its affiliates has germinated through the so-called postmodern age, informing a menagerie of avant-garde isms whose manifestos increasingly prize self-negation, self-deprecation, and a general tongue-in- cheek unseriousness. The invented personalities of the Neoist Manifesto, for instance, engage in faux-angst riddled agit-prop yoked to no clear agenda other than one of obfuscation of anything that might be construed as one. Such is the case when “Karen Eliot” scorns “people so far behind the times as to look for intellectual meanings in a text.”32 This is a sticky stumper. If we take at face value Eliot’s meaning, that we should not look for meanings in a text, we have immediately not taken her implicit advice to not look for meaning in a text in the act of taking her advice, in even thinking that her meaning should be taken so seriously. But, if there is no meaning to the text that says there are no meanings in texts, then…maybe…there are meanings? But if that meaning is to say that there are none… Hmm. The hall-of-mirrors effect of this paradox endlessly replicates an empty rhetoric.

Replication has been one of the defining characteristics of postmodernist art, fitting for an age redundant with the mass production of so many soup cans, Campbell’s or Warhol’s, or both.33 It hardly seems to matter which, for to the Neoists and likeminded ists, art and life have, in an age of mass production, become interchangeable. The Neoist Manifesto, the same one that scorns intellectual meanings in texts, also celebrates “the recycling, editing, rearranging, reprocessing and reusing” of texts and images, whether they be “political propaganda” or “corporate commercial messages,” until they become, as Frederic Jameson puts it, “consumer fetishisms [that] do not seem to function as critical or political statements.”34

The New and Improved Neoist Manifesto says you should not look for meaning in a text, but rather read it like a painting…or does it?

Many postmodern manifestos exhibit this tendency, becoming empty of meaning beyond a blank pastiche of our consumerist environs. In a stagebill for the Lincoln Center Festival we find that Bloomingdale’s has issued Isabella Rossellini’s Manifesto, which instructs us to “Write [our] own manifesto” in its blank spaces.35 Thus it leaves it up to the reader to decide what it will say. Such a mass-produced blank invitation serves to democratize an avant-garde manifesto genre once reserved for cultural elites, much like how Warhol’s mass produced silk-screened soup cans, (mimicking what Henry Ford’s Model-T did for the auto market), made “art” accessible to mere plebs. But in bringing itself to mass consumerist culture, the manifesto has become mass consumerist culture. The critic and philosopher Martin Puchner has noted this indiscriminate, big-box, business friendliness evident in Isabella Rossellini’s Manifesto, where

it does not matter what kind of manifesto you write as long as you write it with Bloomingsdale’s products […] Just as avant-garde aesthetics has been appropriated by institutions such as the Lincoln Center, so the manifesto’s revolutionary gesture has been appropriated by advertisement.

Bill Drummond’s Open Manifesto, too, exhibits mass consumerism’s appropriation of a genre that has been opened up and stripped clean of any tyrannical authorial telos. Appearing online, but otherwise structurally identical to Isabella Rossellini’s Manifesto, in that it is open to input, Drummond’s Open Manifesto lets readers mark empty boxes of cyberspace with content. As long as they limit their content to 100 words or less, their squares of radicalism can be quilted into an ever-growing document. Jim Beattie has made the cut with:

FUCK ART I WANT A BURGER jim beattie

So Drummond, the anti-author, midwifes Beattie’s revolutionary revelation. But the revolution here only turns a metro-station McDonalds’ turnstile, chrome to perfectly reflect naught but a McDo’s advertising mindcrack. Apart from this passive reflection, Drummond’s and Rossellini’s manifestos themselves are silent. But their silences speak volumes about the consequences of the postmodern tendency to view saying as some kind of colonialist, oppressive, soul-crushing enterprise. Where, as Puchner claims, Rossellini’s manifesto “shies away from writing on behalf of anyone, from exerting any kind of authority,”38 and where Drummond’s Open Manifesto seemingly seeks, if anything, to keep Drummond from speaking, a vacuum will always gape until the prevailing tendencies of the environment (i.e. the desire for burgers, in this case) get sucked up into it and the medium becomes the only message.

But why so nervous about saying, I wonder, when this age has run rife with anti- essentialist Karen Eliots, all proclaiming that texts have no meaning, that the link between signifier and signified is arbitrary and always begging to be deconstructed into dust? If we wield such toothless, frail weaponry when we use words, why such reticence? Shouldn’t saying become then like a Nerf sport, where, since the projectiles are divested of the ability to harm, the use of them compensates with increased vigor? But the opposite has been the case. Postmodernist avant-garde groups like the Neoists, Fluxus and others struggle to reconcile the authoritative character of the manifesto with their own agenda of toppling authoritative voices. This concern among manifesto writers seemingly proceeds from concerns underpinning our Rule Three against the use of quotation. The fear is that when we speak, our future selves might be for others what Cicero was for Emerson’s would-be self-reliant scholars, a pedigreed aristocrat canonically oppressing all who had not yet written their own declarations of independence, who thus might allow themselves to be intellectually bullied by the past. This fear is perhaps the main reason why Karen Eliot seems so bent on proclaiming the meaninglessness of words; it is her alibis—if she ever comes to exist and gets called an authoritarian tyrant for having a manifesto and using it as a platform to propound, as would a dictator, an authoritarian agenda (even if it is an agenda of not having one).

So say, or fail to say, the relatively new avant-gardes. But this is not a new conflict, the tension between wanting say and not wanting to oppress. It raged even in the time coffee-coated Franklin. Franklin’s avant-garde manifesto Information to Those Who Would Remove to America describes a democratized New World where the old thrones of Europe have been toppled to the extent that a typical American of his time would

think himself more oblig’d to a Genealogist, who could prove for him that his Ancestors & Relations for ten Generations had been Ploughmen, Smiths, Carpenters, Turners, Weavers, Tanners…& consequently that they were useful Members of Society; than if he could only prove that they were Gentlemen, doing nothing of Value, but living idly off the Labour of others… and otherwise good for nothing…

Fine. Yet, apparently, the consequences of this American genealogical ideal, which revokes aristocratic lineages, could not be reconciled with Franklin’s own manifest authorial ambitions; at the time of his writing his Information he is living in France, for reasons that he divulges while waxing secretly autobiographic.

Hence the natural geniuses that have arisen in America, with such Talents, have uniformly quitted that country for Europe, where they can be more suitably rewarded.

On the surface here he is simply talking about how there are few in America rich enough to purchase the paintings and sculpture that adorn the palaces of the Old World aristocracy, and that painters and sculptors born in the New World have to go back to the Old if they wish to find work. But if we read between the lines a bit, Franklin is admitting that in a purely democratized world, where no one has pedigreed, privileged access to realms of genius, a world consisting entirely of budding Ciceros, Bacons, Lockes, the supply of works of genius will always exceed the demand. For why would Americans subordinate themselves to, by purchasing, the intellectual work of any “natural genius” when they’re supposedly aware of the latent natural genius within themselves? Realizing this supply/demand disparity in America, Franklin “quitted that country for Europe,” which remained a safe haven for the intellectual aristocracy, a place where he could dupe a literate leisure class to prostrate their natural geniuses before his own, where he could reap “suitable reward” for being what he was, a precursor to Napoleon, the self-crowned dictator.

Early American literature runs rife with this conundrum. Hawthorne’s “The Devil in Manuscript” describes the same saturated market of “natural genius” in an idealized New World. “‘What a voluminous mass the unpublished literature of America must be!’ ‘Oh the Alexandrine manuscripts were nothing to it,’ said my friend.”41 Here even an unpublished manuscript becomes an encoded demonic force, a sigil through which the would-be author invokes the Old One, the Old World monarch. For when, out of frustration over its unpublished state, the story’s author Oberon throws his manuscript into the fireplace, it bursts into flames and its pages of smoldering potency are borne aloft through the chimney and disseminated on the wings of ash and smoke. Thus it gets “published” at last. In an orgasmic thrill Oberon, too, becomes a Kaczynskian, Napoleonic destroyer.

My tales!…The Chimney! The roof! The fiend has gone forth by night, and startled all in fear and wonder from their beds! Here I stand—a triumphant author! Huzza! Huzza! My brain has set the town on fire.

Ambitions of authorship will always perpetuate passé Great War violence, will always betray a lust for canonical pedigrees and remain thus un-avant. Unless you keep your “natural genius” to yourself, you are, like Franklin, like Napoleon: you claim to bring us all a new order of things before you don the well-rested-on laurel crown of the old tyrant. So, in the strictest sense, there is no “freedom of the press.” When you send to the press you oppress in your nostalgia for an authoritarian voice.

And, if in the dissemination of our writing we thus destroy the free world, if we

atrophy the arms of the populace by flexing our intellectual muscles for them, if we impoverish by giving gifts to those who would have gifts to give had they not been so used to just receiving them, then even an unpublished manuscript contains potential for powder-keg potentates like Oberon’s imps in an unopened Pandora’s box.

Knowing all this, the writers of the most recent crop of manifestos have ostensibly seen to it that their projects become, as much as possible, exercises in non-existence. Michael Betancourt, for example, has written The ___________ Manifesto of 1996, which allows online readers to fill in blanks in texts culled from Dadaist manifestos.43 And even this isn’t enough to render all authoritarian agendas blank, since, at the end of the manifesto, there is a reset button; even these online participants ultimately undermine themselves. The Stuckist Manifesto, too, perpetuates a Karen Eliotian self-denouncery, spinning and nibbling at the tail of an ouroboros: “Stuckism embraces all that it denounces.”

So clearly, after reviewing these most recent manifestos, one feels inclined to agree with them that erasure is the best antidote for them. And with such conclusions, I feel that I can only advise such a rule of thumb for manifestos in general: not only should they never explicitly or implicitly advise others on what they should or shouldn’t do, say or believe; they should avoid being published at all. Don’t say anything…because everyone deserves a say!

Rule Five

Repeat Rules ONE through FIVE.

To conclude, and to summarize my five points, the fiery pentagram, if you will, that shapes and sharpens this the most radical of radical pamphlets: drink coffee; don’t use explosives; never use French expressions (bien sur!); never involve yourself in dialectics with precedents; never publish, nor write, nor even think your manifesto. For ultimately you will undo the whole project of toppling vainglories, finding it a vainglorious activity, fitting only for radical self-debasement. It will become clear that it is the rupture itself that has become vainglorious and status-quo, rather than the status- quo with which you are rupturing your ties. Then, post-ultimately, you will find such a reposed response of self-undoing, or of not doing the undoing or toppling or rupturing, though seeming at first militantly avant, also signals an epoch of an epic retreat from the leading edge. Indeed, by constantly turning inward in self-reflexive navel erasing, the Situationists and like-minded avant-garders reveal their tactical affiliation with that age old tradition, Monasticism, or the sleeping, or the dead.. The Neoist Manifesto says as much: “Going to sleep may be the most important part of the creative process.”

Though I feel like I have failed my task, I should be going to sleep now, too, since the morning light is slowly steeping through my blinds. But how could I sleep when my bloodstream has become utterly saturated with boiling streams of caffeine? So I will leave myself out on this table for the breakfast of my soon-to-be waking comrades, who have been snoring for what seems a century now, but especially since the end of the Second Great War. O my comrades! Awake! Come spill me. Topple and upturn. Or topple my expectations of being toppled and leave me be. But then, when I am least expecting it, dash me round with your clumsy, naïve, futurist energies. I will bear your past-scorn when it comes. So be not like some immovable Jain, petrified of the slightest offence. Yoke my Gordian neck with both hands. Kiss me when you drink deep. Then out. Open wide your mechanical-anatomical, imperfect human mouth and proclaim, unselfco